The impacts of Typhoon Tino offered a stark reminder. Floods are not solely natural hazards. Instead, they are hydrological imprints of spatial decisions. Land allocation, slope conversion, river encroachment, and watershed disruption manifest their consequences most visibly during extreme weather events.

The approval of Cebu City’s Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) 2023–2032 redirects the public agenda. It moves from legislative formality to the more consequential arena of implementation. The legitimacy of a land use plan is not proven by its passage. Instead, it is validated by the development outcomes it produces. This is especially true when these outcomes are tested by climate, geography, and population pressure.

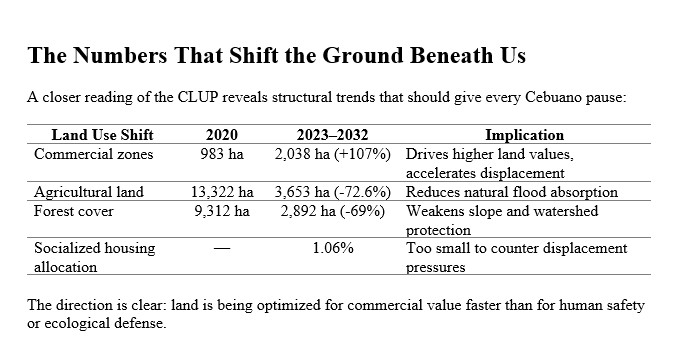

The new CLUP reveals major spatial shifts that carry long-term implications. Commercial land allocation more than doubled, while agricultural lands declined dramatically, and forest areas registered significant reduction. Meanwhile, socialized housing allocation remains strikingly minimal. The pattern points to a clear directional tilt. Commercial land expansion is accelerating faster than ecological buffering. It is also outpacing safe residential capacity.

As land values intensify within the urban core, households priced out of the city do not vanish. They relocate to the margins where land is cheaper and regulations are thinner. In Cebu, this relocation increasingly occurs toward upland barangays, steeper slopes, informal drainage basins, and unengineered terrain. The result is not accidental sprawl but policy-induced spatial displacement, where affordability gradients align dangerously with hazard gradients.

A persistent public misconception aggravates this risk calculus. Many people think that uplands newly classified under NIPAS (National Integrated Protected Areas System) are automatically protected. They believe these areas are free from settlement and land conversion. The law says otherwise. Under DENR Administrative Order 2008-26, Section 10(e), carried into the IRR of RA 11038, NIPAS areas may contain Multiple-Use Zones. In these zones, settlement, agriculture, agroforestry, extraction, and livelihood activities may be permitted. Even land tenure rights can be allowed, subject to the Protected Area Management Plan. In other words, NIPAS is a regulatory designation, not an automatic forest preservation guarantee. Hydrology responds to slope, soil porosity, and tree cover — not legal cartography.

Commerce expands more quickly than contour lines can withstand. Three outcomes converge. Land values rise without a parallel safe housing supply. Ecological buffers shrink faster than drainage systems are upgraded. Disaster risk is redistributed rather than reduced. The city becomes economically attractive yet environmentally fragile — bankable in dry months, breakable in wet ones.

The core policy question is therefore not “Should Cebu grow?” but rather, “Should Cebu grow without slope limits, drainage safeguards, housing balance, and hydrological discipline?” A land use plan that expands markets can be beneficial. However, if it creates flood risks for vulnerable communities, it does not represent a development strategy. It is a liability transfer encoded in zoning policy.

Urban planning must retire the outdated metric of success defined by hectares converted. It should adopt a new standard measured in households protected, watersheds stabilized, and risks prevented. Cities do not fail when the economy slows. They fail when slopes collapse and rivers overflow. Institutions run out of answers during the rainfall test they were meant to anticipate.

Cebu City now stands at a pivotal governance moment. The challenge ahead is not to stop development, but to civilize its direction. We need to build where water can be managed. Settling families in areas where slopes are stable is crucial. We must treat forests as infrastructure. Defending watersheds as life-support systems, not land reserves awaiting extraction, is vital.

The legacy of the CLUP will ultimately be judged by evacuation numbers. It will also be judged by flood marks and the geography of survival when the next typhoon arrives. Investment portfolios or skylines will not determine this legacy.

Progress is not proven by buildings standing in fair weather,

but by communities still standing after the storm.