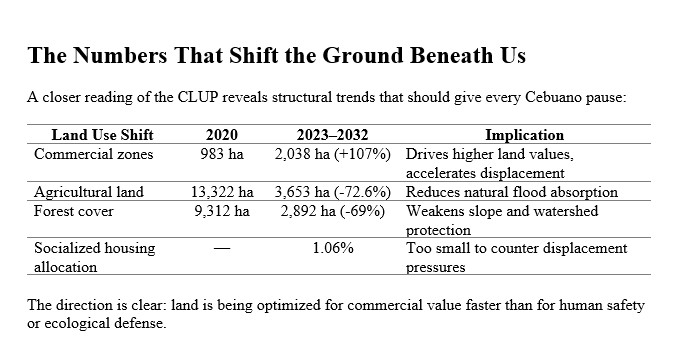

The Cebu City Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) 2023–2032 is often defended on the ground that it significantly expands environmental protection because more than half of the city is now classified under the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS) Central Cebu Protected Landscape. On paper, the figures appear impressive. Forest land drops from 9,312.31 hectares, or 31.08 percent of the city’s land area in 2020, to just 2,892.91 hectares, or 9.65 percent, while a new category—NIPAS CCPL—suddenly expands to 15,102.10 hectares, or 50.40 percent. At first glance, this seems to suggest that forest loss has been offset by a dramatic increase in protected area coverage. In reality, this shift is largely a reclassification, not a conservation gain.

Forest Reduction and NIPAS CCPL Expansion under the Cebu City CLUP (2020 vs. 2023–2032)

| Land Use Category | 2020 Area (ha) | 2020 Share of City (%) | 2023–2032 Area (ha) | 2023–2032 Share of City (%) | Change (ha) | Change (percentage points) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest | 9,312.31 | 31.08% | 2,892.91 | 9.65% | –6,419.40 | –21.43 pp |

| NIPAS CCPL | — | — | 15,102.10 | 50.40% | +15,102.10 | +50.40 pp |

The crucial detail lies in how the NIPAS CCPL is treated internally under the CLUP and its implementing zoning ordinance. The protected landscape is not governed as a single protection category. It is subdivided into Strict Protection Sub-Zones and Multiple-Use Zones. These two sub-zones have radically different legal and ecological effects, yet they are collapsed into a single “NIPAS CCPL” figure in the comparative land-use table. This aggregation creates the impression of expanded protection while concealing a fundamental change in how large portions of the uplands are actually regulated.

Strict Protection Sub-Zones are designed to keep ecosystems intact. They prohibit roads, structures, utilities, and settlement, allowing only limited scientific or educational activity. By contrast, Multiple-Use Zones explicitly allow settlement, agriculture, agroforestry, infrastructure, utilities, livelihood activities, and even extractive uses, subject to conditions, variances, and environmental impact assessments. In practical terms, strict protection constrains development, while multiple use manages development. Treating both as equivalent under a single “protected area” label obscures this distinction.

The land-use data strongly suggest that much of what was previously classified simply as forest in 2020 did not become strictly protected. Instead, it was absorbed into the NIPAS CCPL category and then zoned as Multiple-Use Zone. Only a smaller core—typically the most intact, high-elevation, and least accessible forest blocks—could realistically have been placed under strict protection. Areas closer to barangays, with existing settlements, road access, or development pressure, could not have been placed in strict protection and were therefore zoned as multiple use. This includes large portions of the former forest cover at the urban–upland interface.

This permissive framework is further reinforced by the city ordinance’s treatment of socialized housing within the Multiple-Use Zone. Even within the protected landscape, the zoning ordinance allows socialized housing projects to proceed if they are deemed “essential” and are claimed to have minimal environmental impact. In such cases, the proponent is required to seek variances and exceptions from the Zoning Board, supported by an Environmental Impact Assessment and an Environmental Impact Statement, which must be presented prior to the issuance of an Environmental Compliance Certificate by the DENR–Environmental Management Bureau. The project must also be certified by the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development as a socialized housing project. Where granted special authorization, development is limited to single-detached units on lots of at least 64 square meters and a maximum building height of seven meters.

While these conditions appear restrictive on paper, they underscore the deeper structural issue: land that is otherwise acknowledged as ecologically sensitive and disaster-prone is rendered negotiable through administrative discretion. The safeguards operate at the project level, not at the landscape or watershed level. They assume that environmental risk can be mitigated case by case, rather than avoided altogether through strict land-use exclusion. In a steep, erosion-prone watershed, even low-rise, low-density housing introduces roads, slope cuts, drainage alteration, and cumulative runoff effects that no project-specific EIA can fully neutralize. In this sense, the socialized housing exception does not soften the impact of Multiple-Use Zones—it institutionalizes it.

What Necessarily Went Into Multiple-Use Zones (MUZ)

MUZ is the only CCPL sub-zone where the zoning ordinance allows:

- settlement and relocation sites,

- agriculture and agroforestry,

- infrastructure and utilities,

- agro-industrial activities,

- sale and disposition of titled land,

- and even sand and gravel extraction, subject to EIA.

As a result, any part of the CCPL that:

- already had settlements,

- lay adjacent to barangays,

- had road access,

- or was earmarked for housing, utilities, or livelihood expansion,

could not have been placed in SPZ and was almost certainly zoned as MUZ.

The CLUP zoning maps explicitly identify CCPL Multiple-Use Zones (MUZ) in at least 22 upland barangays, including Adlawon, Agsungot, Babag, Buhisan, Guba, Sirao, Sudlon I and II, Tabunan, Taptap, Toong, and others. These are not peripheral areas. They are headwaters, slopes, and watershed interfaces directly influencing river systems that drain into Cebu City’s urban core.

Functionally, this represents a downgrade in protection. Forest converted into strict protection retains its hydrological and ecological role. Forest converted into a multiple-use zone does not. Even if development is limited to 30 percent of the land area, that 30 percent often consists of roads, access cuts, building pads, and slope modification. These interventions fragment the remaining vegetation, reduce infiltration, increase runoff velocity, destabilize slopes, and raise sediment loads. Hydrologically, a multiple-use zone does not behave like a forest. The correct comparison, therefore, is not forest versus NIPAS, but forest and strict protection versus multiple use. Measured this way, the CLUP reflects a net weakening of upland and watershed protection.

This matters because the uplands of Central Cebu are not just scenic backdrops. They are natural flood infrastructure. Forested slopes slow rainfall, store water, stabilize soils, and regulate downstream flows. When zoning allows these functions to be negotiated away through settlement, roads, utilities, and extractive activities, flood risk is displaced downhill. The cost is borne by lowland communities that experience more frequent and more severe flooding, even as upland development is justified as “controlled” or “sustainable.”

The zoning ordinance itself makes the contrast unmistakable. In the Strict Protection Sub-Zone (SPZ), the City recognizes that certain upland areas must be treated as non-negotiable ecological infrastructure: no roads, no utilities, no structures, and no human activity beyond science and education, precisely because these areas are highly erodible, disaster-prone, and critical for soil, water, and flood regulation. Yet within the same protected landscape, the Multiple-Use Zone (MUZ) operates on the opposite logic. It allows settlement, roads, utilities, land disposition, and even extraction—subject only to conditions and approvals—on the premise that environmental risk can be managed rather than avoided. The contradiction is stark: SPZ accepts that some areas must be left alone to reduce flooding and disaster risk, while MUZ assumes that development in equally sensitive upland watersheds can be negotiated without consequence. Floodwaters, however, do not distinguish between zones. What is permitted in MUZ ultimately undermines what SPZ is meant to protect.

Question of Legal Authority

There is also a legal dimension to this shift that is often overlooked. NIPAS allows multiple-use zones only to the extent prescribed in the Protected Area Management Plan approved by the Protected Area Management Board. Local governments are required to align their plans with these prescriptions, not replace them with their own discretionary zoning regimes. By defining allowable uses, authorizing variances, and substituting zoning-board discretion and project-level environmental assessments for management-plan limits, the ordinance exceeds the authority delegated to the city under national law. In legal terms, this is an ultra vires act—an exercise of power beyond what the law allows. Environmental compliance certificates and impact assessments cannot cure this defect, because procedural safeguards do not legalize land-use policies that are unlawful at their core.

The implications extend beyond technical planning debates. When a land-use plan presents an apparent expansion of protected areas while quietly converting large portions of former forest into multiple-use zones, it creates an illusion of environmental progress. The label changes, but the watershed function deteriorates. In a city repeatedly hit by flooding, this distinction is not academic. It is the difference between treating the uplands as non-negotiable ecological infrastructure and treating them as a managed development frontier.

Ultimately, the question is not whether development should occur in Cebu, but where, how, and under whose authority. When forest protection is diluted under the banner of multiple use, the consequences do not stay in the uplands. They flow, quite literally, downhill.