Why the CLUP Cannot Be Overridden by a Simple Ordinance

In conversations about Cebu City’s development, one dangerous misconception keeps circulating:

“The CLUP is just a tool. The City Council can always pass a new ordinance to change it.”

This idea is not only false —

it is illegal, misleading, and destructive to long-term planning.

The CLUP is not a casual instrument.

It is the foundation of the city’s entire land-use system, backed by national law, Supreme Court jurisprudence, and technical standards.

This explainer breaks down, in clear language, why the CLUP cannot be casually altered, and why it must remain the city’s controlling land-use document.

1. The CLUP Is a Legal Mandate — Not an Optional Planning Tool

The Local Government Code (RA 7160) is explicit:

“Local government units SHALL prepare their comprehensive land use plans…

which SHALL be the PRIMARY and DOMINANT bases for land use.”

(Sec. 20, RA 7160)

Let’s unpack this:

✔ “SHALL” — means mandatory, not optional

✔ “PRIMARY and DOMINANT” — means superior to all land-use ordinances

✔ “Bases for land use” — means all zoning and land decisions MUST follow it

The CLUP is NOT:

- a guideline

- an advisory document

- a flexible policy tool

It is a statutory requirement and it shapes every land-use decision the city makes.

2. The CLUP Is Approved by National Agencies — So a Simple Ordinance Cannot Override It

Under Executive Order 72 and DHSUD/HLURB Rules, the CLUP must pass through:

- Technical planning

- Public consultations

- CPDO review

- City Council adoption

- Regional Land Use Committee (RLUC) approval

- NEDA oversight

This makes the CLUP part of the national planning system.

A regular ordinance:

- does not undergo national review

- does not pass through RLUC

- does not require technical studies

- is not evaluated for hazards, transport, drainage, or environmental impact

Therefore:

A local ordinance cannot overrule a document that required multi-level approval.

The CLUP is a nationally aligned, technically vetted plan.

A zoning amendment is not.

3. The Zoning Ordinance (ZO) Is Only Valid if It Conforms to the CLUP

This is often misunderstood.

The Zoning Ordinance is the implementing arm of the CLUP.

It cannot contradict the CLUP — it must FOLLOW it.

The Supreme Court has said this in black-and-white:

A. Rizal v. Mandaluyong (2005)

Zoning must conform to the CLUP; otherwise, the ordinance is invalid.

B. Fernando v. St. Scholastica’s (2008)

Any deviation from the CLUP requires a CLUP amendment FIRST.

C. Hacienda Luisita v. DAR (2011)

Land-use changes must be consistent with the approved CLUP.

These rulings make one thing clear:

A zoning ordinance that contradicts the CLUP is illegal and void.

So the common LGU practice of “rezoning by ordinance” without CLUP amendment is contrary to law.

4. The CLUP Protects Cebuanos Against Dangerous, Arbitrary, or Politically Driven Land-Use Changes

This is the purpose of having a legally binding CLUP.

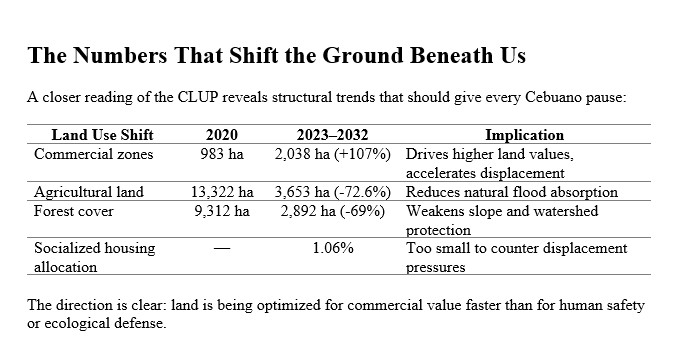

Without a strong CLUP:

- developers can lobby for spot zoning

- upland areas can be converted illegally

- floodplains can be reclassified as commercial

- hazard zones can be opened for construction

- transport systems lose their logic

- water supply planning collapses

- disaster risk increases

- the environment becomes negotiable

The CLUP ensures decisions are based on:

- science

- terrain

- hazard maps

- environmental limits

- water capacity

- transport systems

- long-term growth

—not political influence.

A casual ordinance bypasses all of these safeguards.

5. Changing the CLUP Requires a Full, Regulated Amendment Process — Not a Shortcut

Can the CLUP be amended?

YES — but only through a formal, technical process, not by a simple ordinance.

CLUP amendments require:

- updated technical studies

- barangay consultations

- environmental and hazard assessments

- CPDO evaluation

- Sanggunian approval

- DHSUD regional approval

- RLUC/NEDA conformity

That takes months, sometimes years.

A zoning ordinance alone takes a few weeks —

which is why some LGUs prefer shortcuts.

But these shortcuts are illegal and expose the city to legal, environmental, and governance risks.

6. The CLUP Has Constitutional Weight

The 1987 Constitution guarantees:

“The right to a balanced and healthful ecology.”

(Art II Sec 16)

Land use planning is one of the main instruments used by LGUs to fulfill this constitutional mandate.

If officials bypass, ignore, or override the CLUP, they violate:

- Constitutional policy

- Environmental safety

- National planning standards

- Due process

- Risk reduction principles

This is why the CLUP is not a tool —

it is a constitutional obligation.

7. What Happens If Cebu Treats the CLUP as “Just a Tool”?

The consequences are immediate and severe:

✔ legally void zoning ordinances

✔ invalid permits

✔ increased liability for LGU officials

✔ misaligned infrastructure

✔ worsening flooding

✔ unregulated upland development

✔ breakdown of transport logic

✔ worsening housing crisis

✔ environmental degradation

✔ higher disaster risk

Cebu City cannot afford these outcomes —

not with its limited land, growing population, and worsening climate hazards.

The CLUP Is the City’s Land-Use Constitution

It is:

- mandated by national law

- affirmed by the Supreme Court

- integrated with national planning bodies

- approved through RLUC

- the basis of zoning

- the backbone of environmental protection

- the anchor of water, transport, and infrastructure planning

- the legal safeguard against arbitrary land-use decisions

When officials say:

“We can override the CLUP with a new ordinance,”

they are misunderstanding —

or ignoring —

the entire Philippine land-use legal system.

Cebu deserves better.

Cebu deserves planning grounded in law, science, and long-term vision —

not shortcuts.