The collapse of the Binaliw landfill in Cebu City has been explained away in familiar terms. It has been called an accident. An operational failure. An unfortunate convergence of circumstances. Some have even framed it as a force majeure—an event no one could have reasonably foreseen.

But when examined through the lenses of land-use planning, environmental governance, and disaster risk management, these explanations do not hold.

Binaliw was not an accident.

It was a foreseeable outcome of a planning decision—one that ignored a fundamental principle already embedded in Cebu City’s own Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) and the JICA Roadmap for Solid Waste Management:

No engineering solution can outweigh an inherently risky upland location.

The Real Frame

Public discussion has focused heavily on whether Binaliw was an “engineered sanitary landfill.” That framing misses the point.

Even a perfectly designed landfill cannot defeat gravity, slope instability, rainfall concentration, and watershed dynamics inherent in an upland area. Engineering can only mitigate risk within the limits set by geography—it cannot erase those limits.

The correct question is not whether Binaliw was engineered.

The correct question is why an upland, risk-sensitive area was assigned a high-intensity waste function in the first place.

That question leads us directly to the CLUP and the JICA study.

The CLUP: Risk Was Acknowledged—Then Overridden

Under the Cebu City Comprehensive Land Use Plan, barangays like Binaliw are identified as part of the City’s upland and environmentally constrained zones. These areas are characterized by:

- Slope and landslide susceptibility

- Sensitivity to saturation and runoff

- Strong influence on downstream flooding and disaster amplification

The CLUP recognizes that such areas require low-intensity, risk-compatible land uses, with infrastructure treated as conditional and transitional, not permanent or intensifying.

Yet in practice, Binaliw was allowed to operate as a major disposal site for metropolitan waste, accumulating mass far beyond what an upland area can safely bear over time.

This was not an oversight.

It was a planning contradiction.

Mixed-Use Zoning: Where Risk Became a Policy Choice

The most critical vulnerability in the CLUP lies in its allowance of mixed-use or conditional development in upland areas.

In lowland urban settings, mixed-use zoning can enhance resilience and efficiency.

In upland, environmentally constrained zones, it does the opposite.

Mixed-use zoning in uplands opens the door to intensity creep:

- Risk is acknowledged but not prohibited.

- Projects are approved individually, each appearing compliant.

- Cumulative load is ignored.

- Carrying capacity is exceeded.

A landfill in an upland area is not merely a land use—it is continuous mass loading. Waste is heavy, compressible, water-retentive, and constantly increasing. No zoning flexibility or engineering detail can change that physical reality.

By permitting mixed-use development in upland zones, the CLUP effectively treated risk as negotiable, rather than as a hard limit.

A Warning Issued Long Before the Collapse

What makes the Binaliw disaster even more troubling is that this exact risk was already identified more than a decade ago.

As early as 2015, the JICA Roadmap for Solid Waste Management in Metro Cebu had already reached a clear and technically grounded conclusion: engineering solutions have inherent limits in upland terrain. The study did not merely recommend better landfill design; it explicitly framed upland disposal as a temporary and diminishing option, one that must be progressively relieved of waste load as part of a metropolitan transition strategy.

The 2015 JICA study recognized several realities that remain unchanged today:

- Upland areas are geomorphologically unstable under sustained mass loading;

- High rainfall and steep slopes amplify saturation and failure risks;

- Waste accumulation in uplands contributes not only to local instability but also to downstream flooding and disaster amplification;

- Reliance on existing upland landfills must therefore be reduced over time, not intensified.

In other words, the JICA Roadmap did not assume that better engineering could permanently solve upland disposal risks. It assumed the opposite: that location imposes non-negotiable limits which engineering can only temporarily mitigate.

This is why the roadmap emphasized a phased exit from upland landfill dependence—through waste diversion, metropolitan disposal facilities, and alternative treatment systems. Upland landfills were never envisioned as permanent infrastructure supporting metropolitan waste volumes.

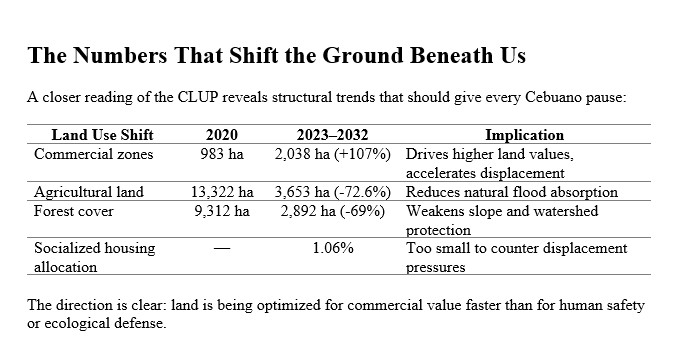

Why the 2025 Cebu City CLUP Must Be Revisited

The collapse of the Binaliw landfill has transformed what was once a technical planning debate into an urgent governance imperative. What is now clear—beyond reasonable dispute—is that the 2025 Cebu City Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) must be revisited, particularly its treatment of upland areas and mixed-use zoning.

This is no longer a question of preference, ideology, or development philosophy. It is a question of whether land-use policy will continue to contradict geographic reality.

Mixed-use zoning is often defended as a modern, adaptive planning tool. In lowland urban contexts, that is frequently true. In upland, environmentally constrained areas, however, mixed-use zoning becomes a risk multiplier.

It allows:

- gradual intensification without clear ceilings;

- project-by-project approvals that ignore cumulative impact;

- reliance on engineering solutions where geography has already imposed limits.

The CLUP’s mixed-use provision, when applied to uplands, converts known natural constraints into negotiable policy choices. Binaliw demonstrates the cost of that conversion.

What Revisiting the CLUP Should Mean (Not Cosmetic Amendments)

Revisiting the 2025 CLUP must go beyond clarifications or tighter permitting language. It requires structural correction.

At minimum, a revised CLUP should:

- Remove or strictly prohibit mixed-use zoning in upland, environmentally constrained areas for high-intensity or mass-loading uses;

- Explicitly classify uplands as protection-priority zones, not development reserves;

- Treat any allowed infrastructure as transitional, with:

- volume caps,

- sunset clauses,

- mandatory exit timelines;

- Align land-use zoning with JICA’s metropolitan transition framework, not short-term disposal convenience.

The Central Policy Lesson

Binaliw has delivered a lesson that planning documents can no longer ignore:

When geography says “no,” zoning must listen.

A CLUP that recognizes upland risk but still permits intensification through mixed-use zoning is internally inconsistent—and now demonstrably unsafe.

A Moment for Course Correction

The call to revisit the 2025 Cebu City CLUP is not anti-development. It is pro-safety, pro-governance, and pro-accountability.

Binaliw should be treated as a planning threshold event—the moment when assumptions were tested against reality and found wanting. To proceed as if nothing fundamental has changed would be to accept that similar disasters are an acceptable cost of “flexibility.”

They are not.

The CLUP must be revised—not because plans failed to exist, but because reality has shown which provisions can no longer be defended.